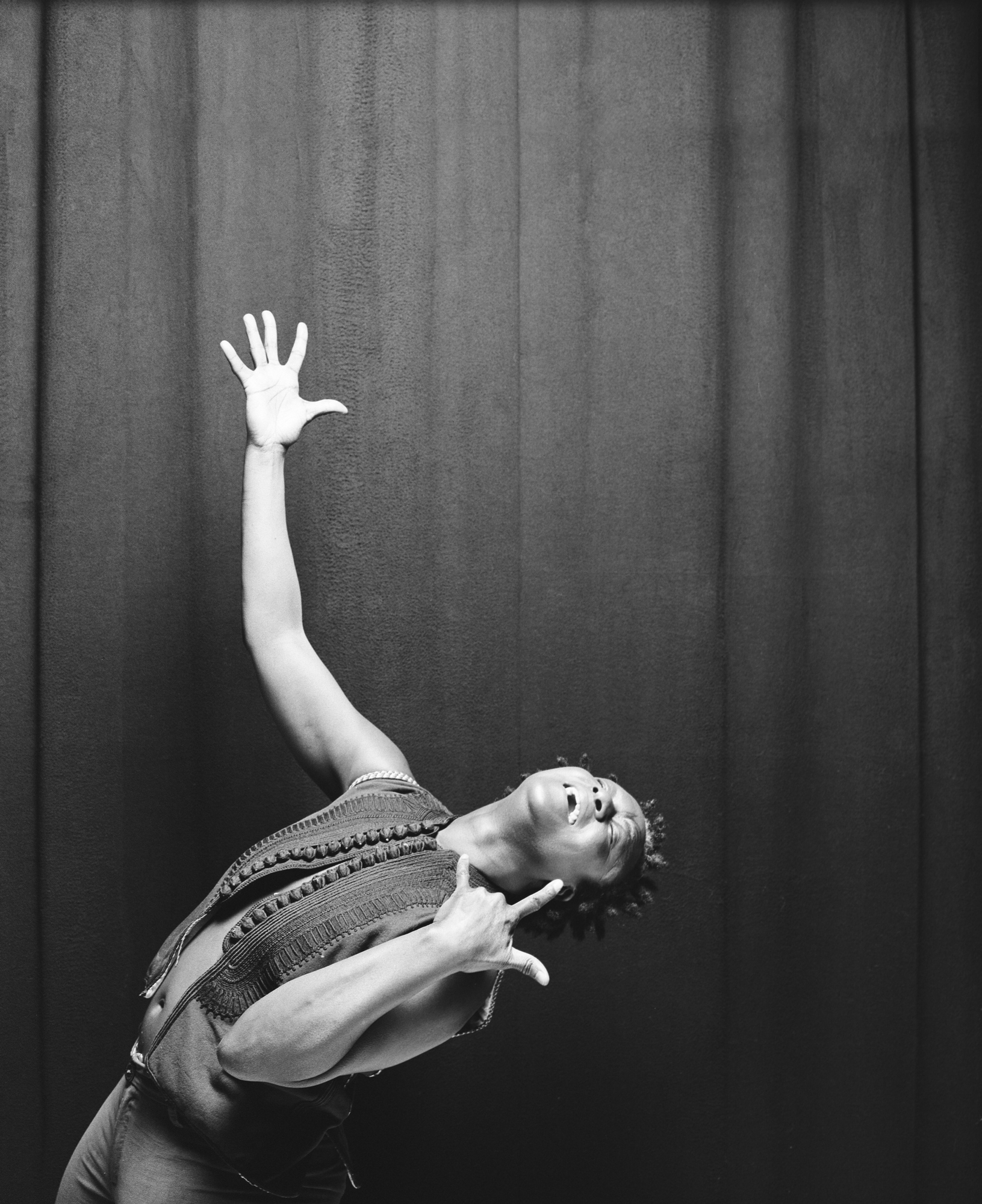

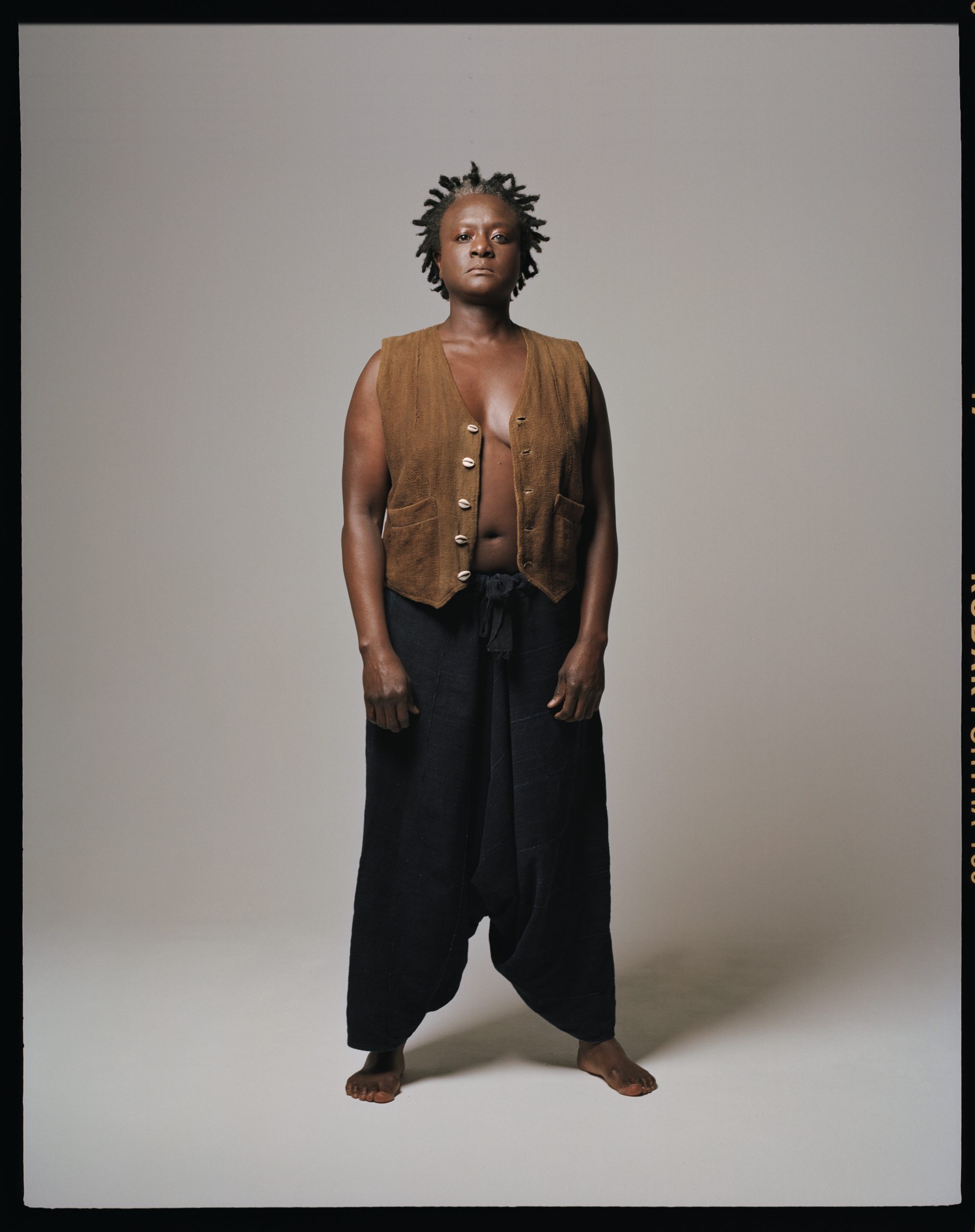

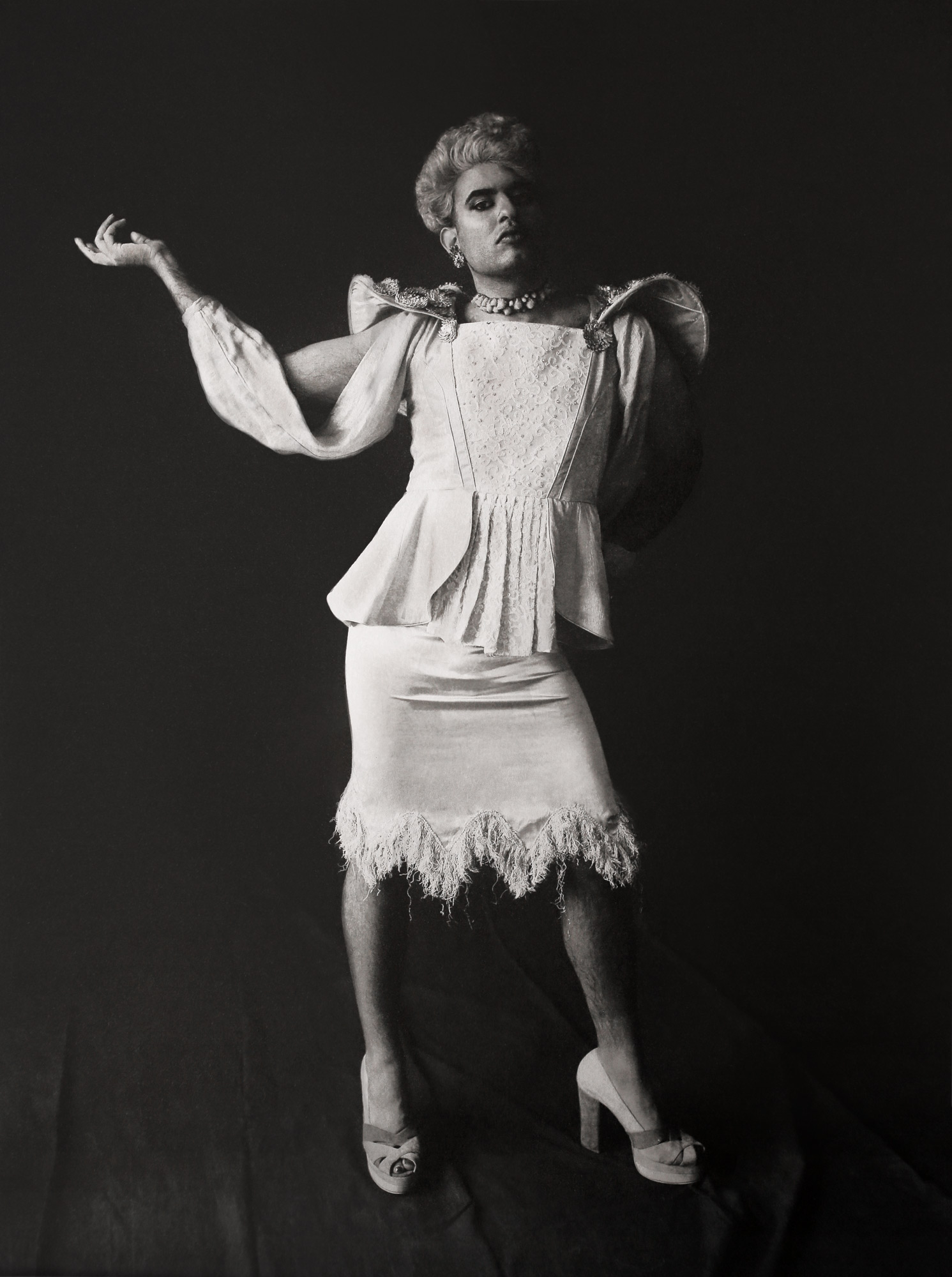

photography

MARY ROZZI

BINTOU DEMBÉLÉ

make up

TIZIANA RAIMONDO

clothing

XULY BËT pour LES VÉTEMENTS

Bintou Dembélé made her Paris Opera debut in 2019 as the first Black woman choreographer and first Black French choreographer to be engaged by the company in its 350-year history. The award-winning production was a revisionist adaptation of Rameau’s baroque opera-ballet “Les Indes Galantes,” and saw hip hop street dancers subverting the colonialist ideas the original libretto was meant to celebrate.

A pioneer of French hip-hop, Bintou is the artistic director, dancer and choreographer of Rualité, a company she created in 2002. Her work explores the issue of the memory of the body through the prisms of the colonial and post-colonial French history. Mixing dance and multiple influences, the company generates dialogue among street dancers, academics, and celebrities who share a commitment to innovation in performance.

EN FRANCE, QU’EST-CE QUE CELA REPRESENTE D’ETRE UNE PIONIER DU HIP HOP COMME VOUS L’ETES ? DE PLUS, EST-CE QUE LE HIP HOP FAIT PRINCIPALEMENT REFERENCE A LA DANCE LA BAS ?

In France, what does it mean to be

a hip hop pioneer as you are?

Also, does “le Hip Hop”

refer primarily to dance there?

Bintou Dembélé: Être pionnière signifie être à la fois témoin et actrice de l’Histoire en train de se faire : découvrir l’émission française H.I.P – H.O.P. à la télévision, puis commencer à danser sur les cartons pour « faire comme », continuer en maison des jeunes et de la culture, se constituer en groupe, se professionnaliser, passer à la scène, voir des gens évoluer, bifurquer, partir, revenir…

Pour répondre à la deuxième partie de votre question, je ne pense pas que le Hip Hop soit réductible à la danse. C’est une certaine forme de commercialisation et de médiatisation qui, en le simplifiant, l’appauvrit beaucoup. Lorsque nous avons commencé à nous regrouper en collectif, la culture Hip Hop combinait, de nombreuses danses avec le rap, le graffiti, le DJing avec un savoir être et un savoir faire, dans une forme d’échange où nous étions témoins les uns des autres.

Bintou Dembélé: Being a pioneer means being both a witness to and an agent of history: watching the French television show “H.I.P. – H.O.P”, imitating moves by street dancing on unfolded cardboard, continuing at the community centre, forming a troupe, going professional, performing on stage, seeing people develop, branch off, quit, come back…

To respond to the second part of your question, I don’t think that Hip Hop can be reduced to dance. That’s a simplification made through a sort of commercialization and mediatization that impoverishes its meaning. When we started to group together, Hip Hop culture combined several dance styles with rap, graffiti, DJing with skills and knowhow, into a back-and-forth where we all had eyes on each other.

“Moreover, in France, those who denounce the under-representation of Afro-descendants find themselves regularly reproached for being obsessed by this issue, for seeing the world exclusively through this prism – for, in a word, for being “racist” themselves.”

VOUS ETES LA PREMIERE FEMME CHOREGRAPHE NOIRE A ETRE ENGAGé A L’OPERA DE PARIS DEPUIS SA CREATION IL Y A 350 ANS

COMME L’A SOULIGNIÉ LE NEW YORK TIMES, CE QUI N’APPARAIT PAS DANS LE MATERIEL PUBLICITAIRE DE L’OPERA OU DANS LA PRESSE FRANCAISE. QU’EN PENSEZ-VOUS?

You are the first black female and first black French choreographer to be engaged by the Paris Opera in its 350-year history. As the New York Times noted, this has gone unmentioned in the company’s publicity materials, as well as in the mainstream French press. How did that feel?

Bintou Dembélé: En France, le mot « race » a été retiré de la constitution en 2018. Cette décision a quelque chose d’ambigu : en même temps qu’elle entend liquider un certain imaginaire historique et biologique porté par ce mot, elle exprime une forme de déni, une difficulté française à penser cette question de la couleur de peau. D’ailleurs, en France, ceux qui dénoncent la sous-représentation des noirs se voient régulièrement reprocher d’être obsédés par cette question, de ne voir le monde qu’à travers ce prisme – en un mot – d’être eux-mêmes « racistes ». Ce déni conduit à l’invisibilisation d’artistes, de communautés colonisées, de pans entiers de la société. De là, la difficulté que nous avons à nous produire sur des scènes contemporaines et à y énoncer nos récits de sorte qu’ils soient lisibles par les publics de ces institutions. De ce point de vue, l’article du New York Times paru au moment des Indes galantes a été pour moi comme une bouffée d’oxygène : il mettait des mots sur ma responsabilité, en tant qu’artiste, de porter ces pans de l’Histoire occultés. Mais il a fallu que ces mots viennent d’Outre-Atlantique. Pendant ce temps, le premier quotidien français titrait : « Les « Sauvages » de Cogitore prennent la Bastille ». Peut-être que si l’on interroge l’autrice de l’article, elle fera valoir que le mot « sauvages » est entre guillemets, que c’est un mot du livret de Fuzelier, qu’elle ne fait que reprendre à la Une les mots du passé. Le problème, c’est que c’est exactement ce contre quoi nous nous sommes battus tout au long du projet : l’idée qu’on ne pouvait reprendre une oeuvre du passé sans porter un regard critique dessus – sous peine de répéter et de perpétuer la violence – l’idée – pour reprendre les mots d’Alfred Döblin – que « l’art n’est pas libre, il agit. » Lorsqu’il a fallu communiquer sur le projet, j’ai l’impression d’avoir été perpétuellement guettée par cette invisibilisation. Il m’a fallu faire une demande pour que mon nom soit remonté dans la distribution, puis pour qu’il soit sur l’affiche, puis pour que les danseurs aient leur biographie dans le programme de salle… A chaque étape, il fallait vaincre les inerties. Lorsque le projet a remporté des prix, le metteur en scène et le chef d’orchestre étaient plus facilement cités que la chorégraphe ou les danseurs, comme si ces derniers formaient une « masse », comme ces tirailleurs africains de la guerre de 14-18 et de 39-45 auxquels il était impossible de rendre hommage nommément.

Bintou Dembélé: In France, the word ‘race’ was removed from the constitution in 2018. There is something ambiguous about this decision: while its intention is to discard historical and biological notions carried by this word, it also expresses a type of denial, a French difficulty with reflecting on the question of skin color.

Moreover, in France, those who denounce the under-representation of Afro-descendants

find themselves regularly reproached for being obsessed by this issue, for seeing the world exclusively through this prism – for, in a word, for being “racist” themselves.

This denial leads to invisibility for artists, colonized communities, and large swathes of society. And what follows is how challenging it has been for us to mount performances on main stages and to tell our stories there in ways that can be understood by those audiences.

Seen from this point of view, The New York Times article that appeared during the run of “Indes Galantes” was, for me, a breath of fresh air: it put into words my responsibility, as an artist, to convey our hidden history.

But those words had to come from across the Atlantic. Back in France, the top newspaper ran this headline: “’Savages’, by Cogitore, storms the Bastille”.

[Translator note: The newspaper replaced the title “Indes Galantes”, an opera by French composer Jean-Philippe Rameau, to “Savages” to echo how aristocrats commented on the revolutionaries who stormed the Bastille prison at the start of the French Revolution. During the Colonial era, Africans were commonly referred to as savages. The former Bastille prison is now the Opera House. Clément Cogitore directed “Indes Galantes”.]

Perhaps when asked, the author of the article would state that word savage was used expressly in quotes, or that it’s a word that appears in Fuzelier’s libretto for the opera itself, or that it simply echoes headlines from history.

But this is the exact problem we confronted while making this project: that performing a work from the past requires a critical eye or else one is doomed to repeat and perpetuate violence – the idea, to quote Alfred Döblin, that “art is not about freedom, it’s about action”.

When the opera was promoted and publicized, I constantly felt threatened by invisibility. I had to make a formal request that my name be listed in the credits, that it be on the poster, that the programme include the dancers’ biographies…I had to fight inertia at every step of the way.

When the project won awards, the director and orchestra conductor were quoted much more than the choreographer and dancers, as if the latter were an unidentified mass, like the African infantrymen of WWI and WWII to whom it was impossible to pay homage by name.

QUE DEVIENS LA DANSE DE RUE, ET TOUT PARTICULIEREMENT LE KRUMP- QUAND VOUS LE METTEZ EN SCENE DANS UN LIEU AUSSI PRESTIGIEUX QUE L’OPERA BASTILLE?

What happens to street dance, especially the politically expressive forms like Krump, when you put it on a stage of prestige like the Paris Opera Ballet?

Bintou Dembélé: Chacune de ces danses est l’expression d’une histoire, d’une actualité. Lorsque ces Street Dances passent de la rue à la scène, lorsqu’elles se déterritorialisent, qu’elles quittent le territoire qui les a vu naître, elles sont forcément perçues très différemment : parce que les spectateurs les voient à travers leur propre regard, à travers le filtre de leur propre expérience. Du reste, c’est le lot de toutes les cultures nées à la marge lorsqu’elles se déplacent vers le « centre » : certaines perdurent, d’autres s’éteignent. C’est l’histoire du Hip Hop, du rock, du punk. De tous ces courants qui se confrontent à un moment donné à la question de leur institutionnalisation ou de leur commercialisation. Pour ma part, j’invite à remettre en mouvement, à se laisser la possibilité de vivre ces déplacements comme des réinventions. La question est : comment chaque personne peut préserver le fond de cette culture tout en le renouvelant ?

Bintou Dembélé: Each of these dances is an expression of a story, of lived experience. When Street Dances go from the street to the stage, when they deterritorialize, when they leave behind the places that gave birth to them, they are necessarily perceived very differently. Audiences watch from their own perspective, from the filter of their own experience.

Beyond that, it’s simply the fate of marginal cultures when they move towards the centre, some endur, others die out.

It’s the story of Hip Hop, of Rock, of Punk. Of all movements confronted by the possibility of institutionalization or commercialization.

For me, I encourage untethering and leave myself open to the possibility of living these displacements as reinventions. The question is: how can each person preserve the core of this culture while also renewing it?

“…performing a work from the past requires a critical eye or else one is doomed to repeat and perpetuate violence – the idea, to quote Alfred Döblin, that “art is not about freedom, it’s about action.”

AVEC VOTRE COMPANIE RUALITZé VOUS EXPLOREZ LA MEMOIRE DU CORPS A TRAVERS LE PRISME DE LA COLONISATION ET LA POST COLONISATION. Où sommes-nous actuellement?

With your own company, Rualité, you explore the issue of memory of the body through the prisms of the colonial and post-colonial French history. Where are we now ?

Bintou Dembélé: Pour répondre à cette question – où en sommes-nous ? – je voudrais dire d’où je viens, revenir au chemin que j’ai parcouru entre le moment où je me suis mise à danser et le lieu d’où je parle aujourd’hui. Pour moi, commencer à danser était synonyme de passer de la timidité à une forme de rage intérieure. La danse m’a permis de traduire cette rage. Par la suite, en me professionnalisant, je me suis rendu compte que cette rage s’était transformée en urgence : en urgence de « dire », comme si danser ne suffisait plus. Comme toute danseuse, au cours de ma carrière, il est arrivé que je me blesse. De blessure en blessure, j’ai fini par prendre conscience que nous avions un rapport violent à notre corps. Pourquoi ? D’où venait cette violence ? J’avais besoin de comprendre ce qui nous hantait pour comprendre pourquoi nous habitions notre corps aussi violemment. C’est à ce moment que j’ai commencé à m’intéresser à cette histoire coloniale – qui nous empêche d’avancer et de nous construire – et que j’ai placée au centre de mon travail. J’imagine que c’est la différence entre ce qu’on appelle l’art ou la culture, et la nécessité.

Bintou Dembélé: To respond to your question “where are we now”, I would like to talk about where I come from, to look back at the path I pursued from the moment I first started dancing to the place where I am today. For me, starting to dance was synonymous with moving from shyness to something akin to internal rage. Through dance, I could translate that rage. Then, when I began to dance professionally, I realized that that rage had been transformed into an urgent calling, an urgency “to speak”, as if dance itself no longer sufficed.

Like all dancers, I’ve suffered injuries. One injury after another. Eventually, I became aware that we have a violent relationship to our bodies. Why? Where does this violence come from? I had to understand what haunts us to understand why we live in our bodies so violently. It was then that I started to be interested in the history of colonization — that history that prevents us from moving forward and from building ourselves up – and that I placed it at the center of my work. I suppose it’s the difference between what we call art or culture and necessity.

Est-ce que vous refusez d’appliquer les étiquettes « d’art » et de « culture » à vos créations ?

Do you reject labeling your work “art” or “culture”?

Bintou Dembélé: Il y a eu, à un moment donné, la nécessité d’identifier, de nommer cette « culture » Hip Hop qui a investi différent champs – la danse, le rap, le DJing… Pour moi, il s’agit moins d’une culture que d’une forme de rite que j’ai besoin de réinventer et qui me permet d’être en phase avec le présent.

Bintou Dembélé: At one point, it was necessary to identify and name one “culture” of Hip Hop, even though it was comprised of the different worlds of dance, rap, DJing… For me, it’s less about a culture than about a kind of ritual that I need to reinvent and that allows me to be in synch with the present.

Quel sens donnez-vous à ce mot – « rite » ?

What meaning do you give to the word “rite”?

Bintou Dembélé: Je suis d’origine sénégalaise. Mes parents, mes grands-parents, mes arrière-grands-parents sont nés sur le continent africain. Je suis la première de ma famille à être née en France. Je me suis construite avec cette double identité. Au Sénégal, la musique et la danse servent aussi à fêter une naissance, à célébrer un mariage, à dire adieu à un mort. Cette dimension rituelle m’habite profondément. Elle est constitutive de mon approche de la chorégraphie, du geste, de mon rapport à la voix. Mon histoire est aussi marquée par mon enfance en banlieue parisienne. J’y ai appris à danser : sur des cartons puis dans une MJC où nous nous sommes constitués en groupe. Je suis ensuite passée à la scène en devenant intermittente – ce statut typiquement français dont j’ai bénéficié. Je suis donc à la croisée de ces histoires mais je ne veux pas occulter la première. Je navigue entre les cultures populaires de tous les continents.

Bintou Dembélé: I am of Senegalese origin. My parents, grandparents, great-grandparents were all born on the African continent. I am the first in my family to be born in France. I built myself with this double identity.

In Senegal, music and dance are also used to celebrate a birth or a marriage or to mourn. This ritual dimension lives in me deeply. It constitutes my approach to choreography, gesture, my relationship to the voice.

I am also marked by my childhood in a Parisian suburb*. It’s where I learned to dance: first on the street, then in the community center where we formed our first troupe. Then, I became a freelance stage performer – an employment wage, special to France, that I lived on.

So I am at the crossroads of those two histories, but I don’t want to hide the first. I navigate popular culture of all continents. *[Translator note: In Paris, public housing is mainly in the suburbs.]

QUEL EST VOTRE REVE POUR VOTRE CHOREGRAPHIE, QUELLE PLACE VOULEZ VOUS QU’ELLE PRENNE DANS LE MONDE et son évolution du point de vue de votre POV politique?

What is the dream for your choreography, its place in the world and its evolution from the perspective of your political POV?

Bintou Dembélé: Je crois que si j’ai encore plaisir à travailler la chorégraphie et le mouvement, c’est parce que j’ai toujours voulu apprendre, désapprendre, réapprendre. Si, un jour, je n’ai plus rien à dire, je laisserai la place à quelqu’un d’autre. J’espère avoir l’intuition de me retirer au bon moment, de savoir quand il sera temps de retourner dans l’ombre. Déjà, aujourd’hui, je danse moins. J’ai décidé de laisser de l’espace à d’autre, de m’exprimer autrement. Avoir la possibilité d’écrire, de poser sur le papier ce que je vis en ce moment, serait une façon pour moi de continuer d’être en mouvement. J’ai vécu une jeunesse différente de celle que vivent les jeunes d’aujourd’hui. Être à l’écoute du temps me permet de me renouveler, de me repenser et de me redéployer à nouveau. Je ne peux que rêver d’être intuitivement proche, à l’écoute de ce mouvement intérieur.

Bintou Dembélé: I think that if I still enjoy choreography and working with movement, it’s because I’ve always wanted to learn, unlearn, and relearn. If one day I have nothing left to say, I’ll make room for someone else. I hope I’ll know when it’s time to step back, when it’s time to return to obscurity. Already today, I dance less. I’ve decided to leave room for others and to express myself differently.

To have the possibility to write, to put to paper what I’m living in this moment, would be one way for me to continue to explore movement. I had a childhood that is very different from what kids are experiencing today. Being open to the moment, I can renew, rethink, and reassign. I can only dream of being intuitively close, listening to this interior movement.

“Les Indes Galantes,” directed by Clément Cogitore, with choreographers Bintou Dembélé, Grichka et Brahim Rachiki

A precursor to the Opera Paris production, the film adapts part of Rameau’s ballet, mobilizing a group of Krump dancers, an art form born in Black neighborhoods of Los Angeles in the 1990s. K.R.U.M.P. (Kingdom Radically Uplifted Mighty Praise) occurred in the aftermath of the beating of Rodney King and the riots, as well as police repression it triggered. Young dancers started to embody the violent tensions of the physical, social and political body.

Dancers : OZEE AKA JDOT SOSA, SISTA SOSA AKA GIRL G, SOULJA GEE OH AKA SHIGAWARA, BLANCHE et SOSA du groupe STRANGE BANGERS. TIGER LIL GULLY BERTH, FLIPSIDE, BABY GRICHKA/ PRINCE TIGER, IVANOVA/SPIRITZ et KidNY du groupe MADROOTZ / MONSTA NY MADNESS. CYBORG, WOLF, JAMSY, NADEEYA et BOY MIJO du groupe REALUNDERGROUND / X2BUCK. NOSCRIPT et P.SNIPER AKA TRAFULHA. Crowd Leaders : WRESTLER, ITACHI et LADY DEL DJ : MORMUZIK ZER