words

OLIVIA LINDSAY AYLMER

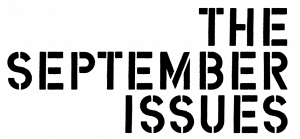

The New Rules of Digital Seduction

printed issue

SEDUCTION

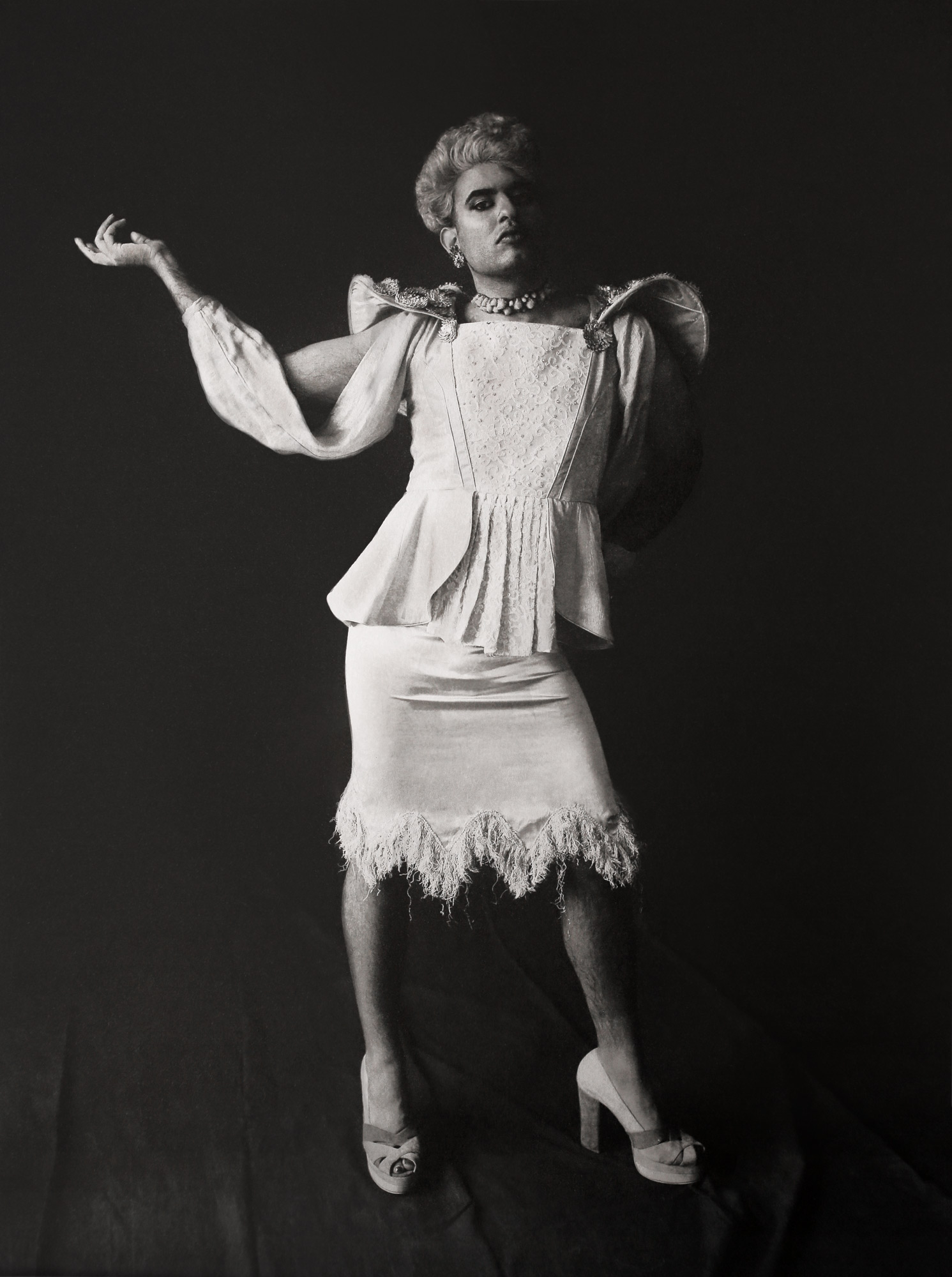

illustrations

M RASMUSSEN

photography

ANASTASIYA OSTASHEVSKA

#METOO dating landscape, it’s hi time we rethink how we acquire what we desire- especially when we start from behind the screen. writer Olivia Lindsay Aylmer discusses the current digital dating landscape and interviews women such as @H_E_R_S_T_O_R_Y and personals founder KELLY RAKOWSKI, and dating editor at elite daily, HANNAH ORENSTEIN.

I. SEDUCTION IS DEAD—OR IS IT?

If you’ve faced singledom in the past decade, chances are you’ve crafted an online dating profile, or at least helped a friend tweak theirs. And it’s likely that, in the process of putting yourself out there in the hopes of meeting someone worthy of your real-life presence, anxiety, frustration, or sheer emotional burnout have served as bummer side effects. Cynics will say that it’s impossible to build an authentic connection on platforms whose very framework raises questions about performativity and alienated artifice. Even those who manage to make it to the other side sometimes bear an unshakeable sense of embarrassment when asked how they met their new Person, if the answer is “the apps”. And, no surprise, dating apps attract as many offensive, sexist, violently motivated trolls as the rest of the Wild West Internet.

That’s why female-led innovation and leadership matters.

For several years now, Whitney Wolfe Herd, 29, has been at the forefront of vastly improving the digital dating experience for women as founder and CEO of Bumble, founded in December 2014. After her time at Tinder—the popular dating app she cofounded and, ultimately left in 2014, claiming sexual harassment by her co-founder and ex-boyfriend Justin Mateen, who was suspended from the company, with Wolfe Herd settling for a reported $1 million—a new app idea emerged out of a seemingly simple, yet powerful, premise: what happens when women make the first move?

The key to Wolfe Herd’s swiftly growing success—as of July 2018, Forbes values the company at $1 billion—lies in her hunch that, when women feel empowered to shift passé power dynamics by pursuing a date (or friend or collaborator) on the app, who knows how far that confidence will carry into their offline lives? If the 100,000 downloads Bumble garnered within its first month is anything to go by, excitement around a new kind of connectivity conduit, explicitly shaped by women, is palpable.

For Wolfe Herd and her Austin, Texas-headquartered team, the long game is so much greater than restoring women’s sense of control over their dating lives: Bumble welcomes its users to seek out platonic and professional relationships, via their BFF and Bizz features, with as much curiosity and enthusiasm as they would a romantic one. Since its start, Wolfe Herd has approached Bumble’s growth by thinking about ways to engage users both on and off the app. From its 2017 pop-up ‘Hive’ space in New York City to hosting events centered on female entrepreneurship and navigating (of course) relationships, the company considers women’s holistic, multi-faceted needs and desires for genuine connection—and meets them in ways one must experience to fully appreciate.

As Wolfe Herd told Vogue in an October 2017 interview, “Bumble has tried to really take away the notion that going right or left on someone has to be a hypersexual thing.” Now we’re getting somewhere.

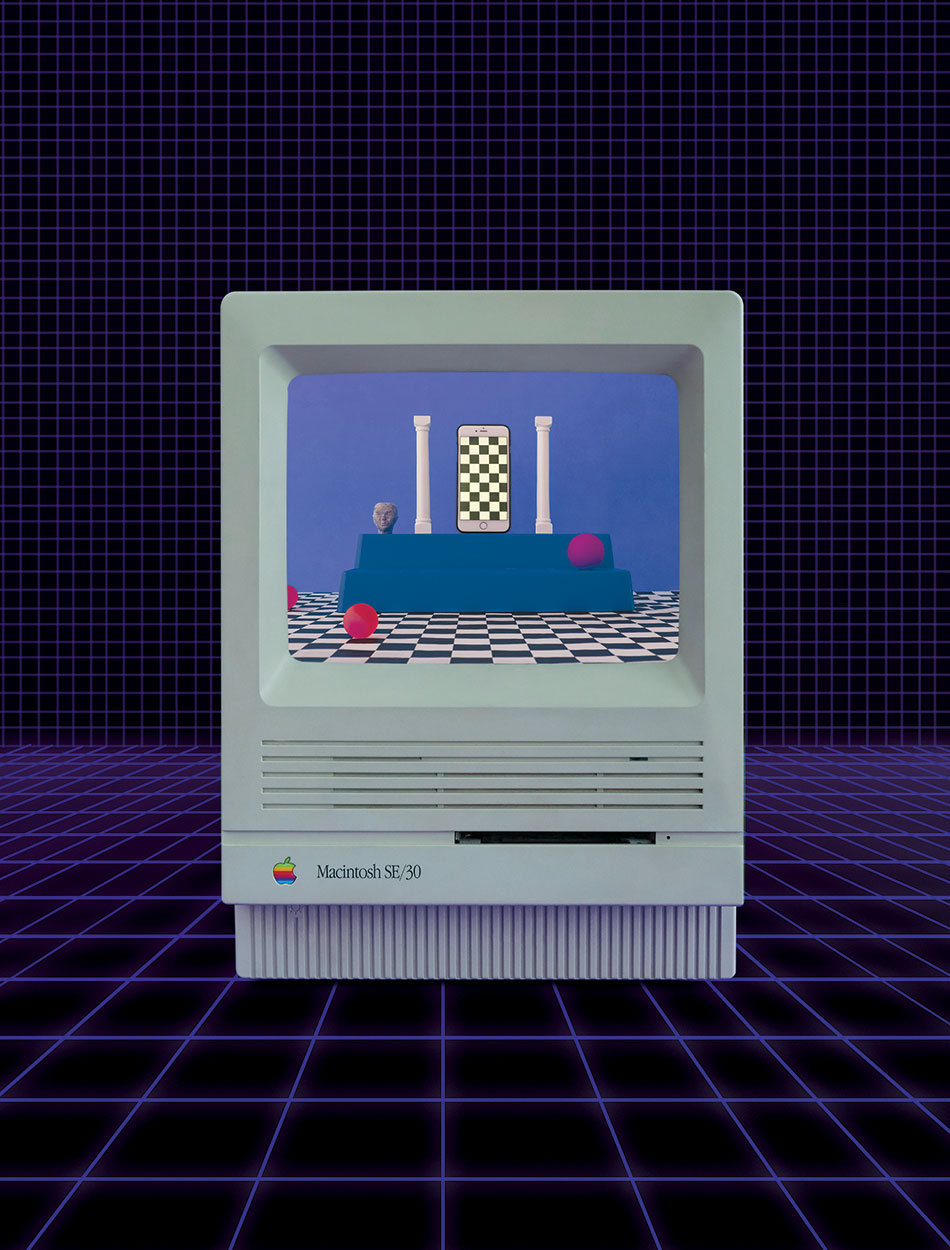

II. PAST

Seeking connection through technologically enabled means is, of course, nothing new. While the platforms may have grown in sophistication and personalization, and shifted to our smart phone-wielding fingertips, the underlying urge to make the process of meeting new matches more efficient goes back to at least 1964. That’s when Joan Ball, an early pioneer in computer dating and social networking realms, founded the St. James Computer Dating Service in England.

Long before we were swiping left and right alone in our bedrooms, considering common interests and cuteness of photos, Ball started her service (which would eventually come to be known as Com-Pat, short for “computerized compatibility”) based on the premise of matching people by what they didn’t want in a relationship. Through the remainder of the 1960s, her hunch proved a hit.

You may be more familiar with Operation Match, Ball’s American-founded counterpart, which was born in 1965 by three Harvard students (Jeff Tarr, David Crump, and Vaughan Morrill) and an outside partner (Douglas Ginsburg). The group developed the idea as a remedy for what they saw, as reported in a 1965 Harvard Crimson article, as “the irrationality of two particular social evils: the blind date and the mixer.”

That’s where computers as matchmakers come in.

Initial preferences were noted via paper questionnaire (read: no profile pictures), then punched into cards, and processed on an IBM 1401 computer. In return, participants received a printout with addresses primed for snail mail.

Just four years prior, the New Yorker heralded the arrival of just such computerized intimacy conduits. For their Valentine’s Day 1961 cover, the cartoonist Charles Addams illustrated a larger than life, light-emanating computer ejecting a delicate valentine for its solo female operator to assess. As historian Marie Hicks pointed out in her extensive 2016 survey of early computer dating, published in Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, the magazine’s cover choice conveyed some of the tech-centric anxieties and expectations swirling around what computers might make possible re. human connection, for better or worse.

Although decidedly analog, early services like Com-Pat and Computer Match nevertheless shifted the ground beneath us when it came to surveilling matches and sending one’s desire for a relationship (or at the very least, meeting for drinks) out into the ether. And if the array of present offerings are anything to go by, digital dating’s ubiquity and social acceptability only evolved and expanded in the years that followed.

III. PRESENT

If you’ve faced singledom in the past decade, chances are you’ve crafted an online dating profile, or at least helped a friend tweak theirs. And it’s likely that, in the process of putting yourself out there in the hopes of meeting someone worthy of your real-life presence, anxiety, frustration, or sheer emotional burnout have served as bummer side effects. Cynics will say that it’s impossible to build an authentic connection on platforms whose very framework raises questions about performativity and alienated artifice. Even those who manage to make it to the other side sometimes bear an unshakeable sense of embarrassment when asked how they met their new Person, if the answer is “the apps”. And, no surprise, dating apps attract as many offensive, sexist, violently motivated trolls as the rest of the Wild West Internet.

That’s why female-led innovation and leadership matters.

For several years now, Whitney Wolfe Herd, 29, has been at the forefront of vastly improving the digital dating experience for women as founder and CEO of Bumble, founded in December 2014. After her time at Tinder—the popular dating app she cofounded and, ultimately left in 2014, claiming sexual harassment by her co-founder and ex-boyfriend Justin Mateen, who was suspended from the company, with Wolfe Herd settling for a reported $1 million—a new app idea emerged out of a seemingly simple, yet powerful, premise: what happens when women make the first move?

The key to Wolfe Herd’s swiftly growing success—as of July 2018, Forbes values the company at $1 billion—lies in her hunch that, when women feel empowered to shift passé power dynamics by pursuing a date (or friend or collaborator) on the app, who knows how far that confidence will carry into their offline lives? If the 100,000 downloads Bumble garnered within its first month is anything to go by, excitement around a new kind of connectivity conduit, explicitly shaped by women, is palpable.

For Wolfe Herd and her Austin, Texas-headquartered team, the long game is so much greater than restoring women’s sense of control over their dating lives: Bumble welcomes its users to seek out platonic and professional relationships, via their BFF and Bizz features, with as much curiosity and enthusiasm as they would a romantic one. Since its start, Wolfe Herd has approached Bumble’s growth by thinking about ways to engage users both on and off the app. From its 2017 pop-up ‘Hive’ space in New York City to hosting events centered on female entrepreneurship and navigating (of course) relationships, the company considers women’s holistic, multi-faceted needs and desires for genuine connection—and meets them in ways one must experience to fully appreciate.

As Wolfe Herd told Vogue in an October 2017 interview, “Bumble has tried to really take away the notion that going right or left on someone has to be a hypersexual thing.” Now we’re getting somewhere.

VI. FUTURE

Riding the subway one day, as my mind wandered to the topic of finding love, or something like it, in the Internet Age, I found myself distracted by a wall of ads for none other than one of the OG apps: OKCupid. Their tagline was short and sweet and oh so accurate: “Dating deserves better.”

Yet it was the striking visuals and witty copy accompanying said tagline that made me look closer. In vibrantly saturated, beautifully art-directed scenes, couples of diverse orientations appear happily DTF: that is, down to fire up the kiln, fantasize about 2020, flea market together, or fall head over heels. In a 180-degree repurposing of the crude, timeworn adage “down to fuck,” the team at ad agency Wieden+Kennedy New York replaced the third word with refreshing alternatives to the standard script of hooking up early into a relationship. (Which is, of course, completely fine if both parties agree that’s what they want! Though it’s certainly not the only viable next step after first-meet.)

Could refreshing the marketing around dating apps help us to reframe our use of them and the potentially positive experiences they contain? OKCupid thinks so.

“We set out to really explore what happened to chivalry and courtship and how modern-day dating seemed to be on a bad trajectory,” copywriter Ian Hart told adweek in January. “When we say dating deserves better, what we’re really saying is people who date deserve better. Because I mean, they really do. Modern dating treats emotions like a disposable commodity. Anyone who’s been single knows this. It’s an aspiration to treating people like people.”

So ad campaigns are one way to put modern seduction in a fresh context, but what about a new app to fill previously unmet needs entirely? Enter photo editor Kelly Rakowski, whose name you may recognize as the founder of the Instagram account @h_e_r_s_t_o_r_y, a collection of images drawn from early 1800’s to late 1990’s lesbian culture.

It’s a balmy evening in July when Rakowski, 38, and I meet outside a coffee shop on the cusp of closing in her Brooklyn neighborhood of Park Slope. If she appears slightly dazed, it’s for good reason. Her campaign to bring Personals, a new kind of text-based dating platform and community, to life has clearly struck a nerve, having met its Kickstarter fundraising goal, and then some, of $47,779 with 1,736 backers just a couple days prior. Suddenly, what started as a fun, lighthearted project-turned-Instagram account between friends and managed via Google Docs appears primed to shake up the queer dating landscape for the better.

Inspired by old-school newspaper “personals,” and created for lesbians, QT (queer-trans), and non-binary, LBTQIA-identified people, the format draws a nostalgic page from the playful, witty, and often humorous looking-for-love ads Rakowski initially discovered in the archives of On Our Backs, the first women-run erotica magazine geared toward a lesbian audience.

Rakowski envisions the full-fledged app as a nucleus for what she terms “slow dating”: a respite for those who’ve grown weary of traditional selfie-swiping culture to more thoughtfully, and specifically, articulate their desires—whether for a romantic relationship, a friendship, or players for a dyke soccer team (it’s happened!), depending on the person.

“When I first showed one of my friends, she was like, “oh, finally, I can just see what people are wanting. They’re so direct,’” Rakowski tells me. On Tinder, which she admits, with a laugh, she “used hard” about four years ago, “you didn’t know if you should write something or not, because it’s too embarrassing—but this is all about being up front. You have to be honest with yourself. I just really think when you write something down, it really can come true to life in a different kind of way.”

One key ingredient in the cult following that has built up around Personals lies in its embrace of language, a critical means of expressing queer desire in all its nuanced multiplicities. “The personal really does compliment the way people describe themselves,” Rakowski explains. To that end, she regularly receives DMs from people who have recently come out, who tell her that “just reading how people talk about themselves is really helpful.”

What sets Rakowski’s vision apart from preexisting apps is her focus on fostering a community larger than the sum of individual matches. In addition to hosting speed dating events and full-fledged parties (the most recent of which unfolded in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, complete with cherry-red streamers and a disco ball) that bring the app to life beyond its interface, Rakowski would like to develop new tools to help guide what happens after two people meet via Personals, whether they live in Los Angeles or a rural, midwestern town. As she sees it, the key to navigating online dating comes down to setting clear intentions for yourself and staying open to unknown possibilities. It’s about “being true, and not playing games. Because if you meet someone and it works, it just works. But you really need to know yourself—and know what you want.”

V. NEW RULES

As we look to the future of digital seduction, there’s no doubt that the underlying uncertainty and vulnerability that accompanies making one’s desires known to the wider world will remain, simply, part of the process. Yet there’s a power inherent in recognizing our ability to choose exactly how we engage with said process.

As Hannah Orenstein, author of the novel Playing with Matches, the dating editor at Elite Daily, and a former matchmaker, wrote me by email this summer, “Dating was difficult prior to the rise of dating apps, and it’s going to be difficult in a new way when the dating landscape inevitably shifts again in the future. It’s never easy to find authentic, satisfying connections.”

While Orenstein understands people’s frustrations with the medium, she does not feel it’s productive to blame dating apps, which, she acknowledges, have permanently changed the ways in which we connect.

Instead, Orenstein recommends focusing our energy on dating and connecting with others in a way that feels right to each of us. “If you’re feeling burnt out, put yourself on a dating detox and delete dating apps until you feel ready to use them again. If you’re bored by having the same kinds of conversations or experiences over and over again, switch up your approach: try using a different app, refresh your profile with new photos and language, use new conversation starters (or challenge yourself to make the first move, if you don’t typically do that), or swipe right on people you don’t consider your ‘type,’” she suggests.

And if you find you truly hate swiping, delete the app. Go outside. See what happens. Who knows who will cross your path?

It must be noted that, as the cultural conversation surrounding sexual assault and misconduct continues to unfold, the heterosexual dating landscape in particular still has some major growing pains to work through. Orenstein cited a joint Glamour and GQ study of men ages 18 to 55, which found that 47 percent of men surveyed said they had never discussed the #MeToo movement with anyone, and only 38 percent said that #MeToo encouraged them to re-examine their sexual past. “The conversations I’ve had with women in my own life haven’t changed,” Orenstein told me. “Just as always, some men are proactive about discussing consent and safe sex, demonstrate true respect for their partners, and seek to examine their own behavior; other men leave a lot to be desired. The dating landscape can’t and won’t progress in a healthy direction unless we’re all on the same page.”

Exactly how seduction will look 10, 20, 30 years from now remains to be seen. But what if it no longer centered on one person wielding power over another? Maybe seduction in 2018 and beyond looks like drawing someone out of their shell, because we truly want to know them, and allowing ourselves to be drawn out in the process, because we’re open to showing someone else who we are, idiosyncrasies and all. Maybe it’s as simple as remembering the forces of attraction that meditate our interactions: what we put out, we get back in return.

Let’s talk to each other. Let’s stop hiding behind shame. Let’s bring our full selves to the table. Let’s take responsibility for our words, our actions, our intentions. Let’s remember that the Internet is one way to connect, but not the only way. Let’s maintain our personal standards of respectful, ethical behavior, and make those standards clear to others. Let’s remember there’s a human being on the other side of the screen. Let’s leave room for intuition, chance, and the cosmic connections that draw certain people together at seemingly random times.

By inviting and sharing more honesty, curiosity, and authenticity in the romantic realm, there’s room for a new kind of seduction to thrive, on and offline, in the years ahead. Now it’s up to each of us to recode it.