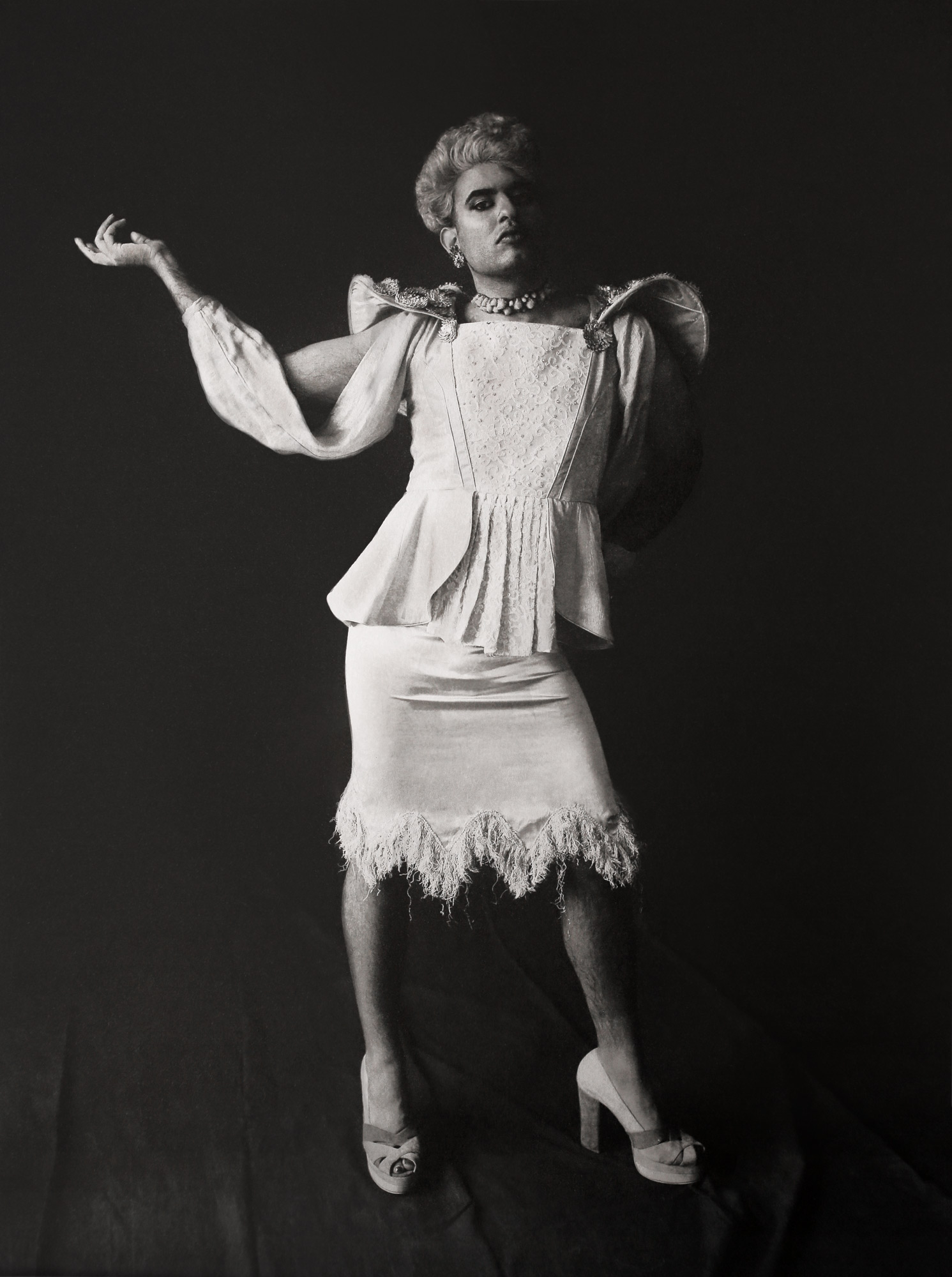

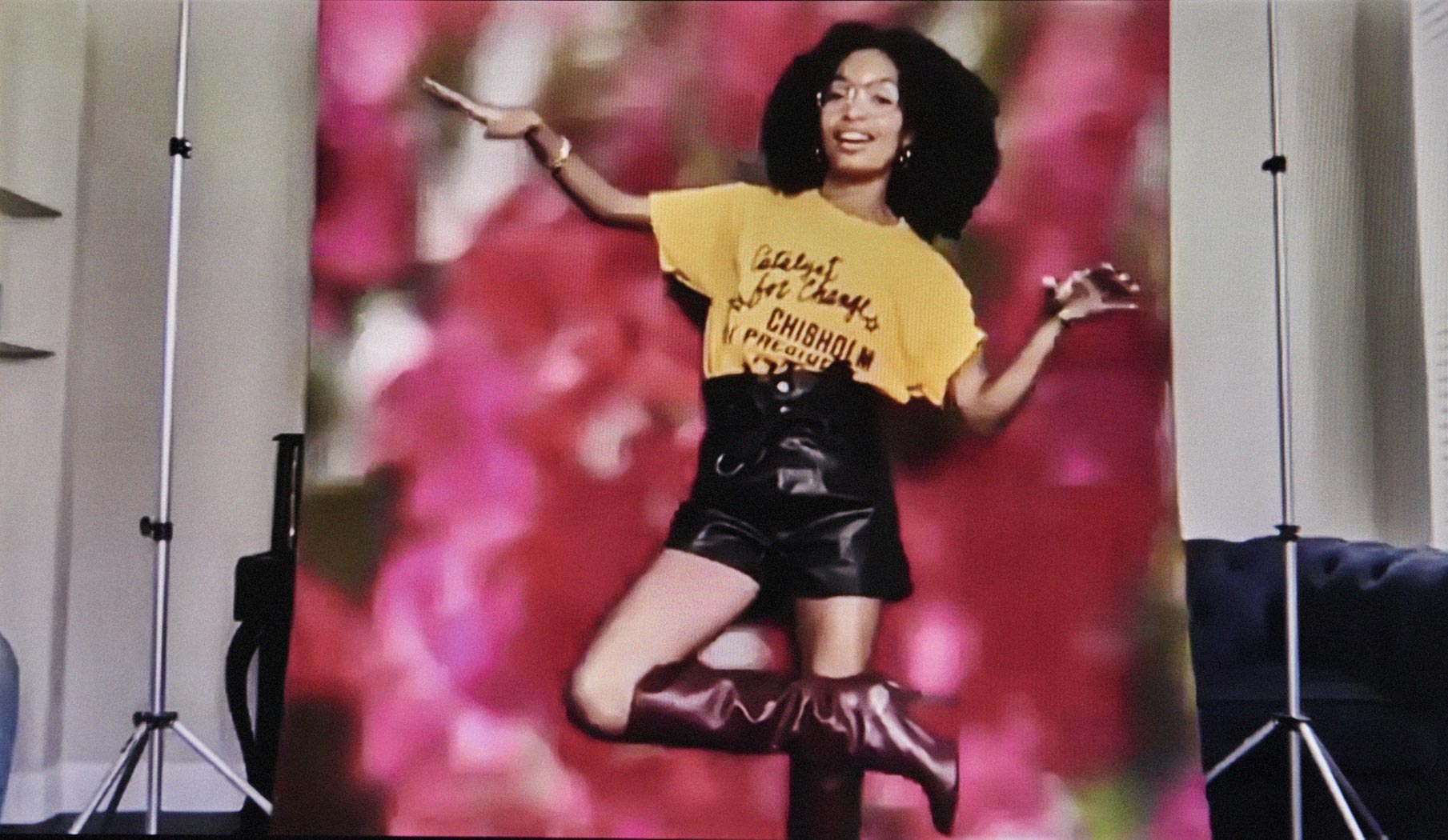

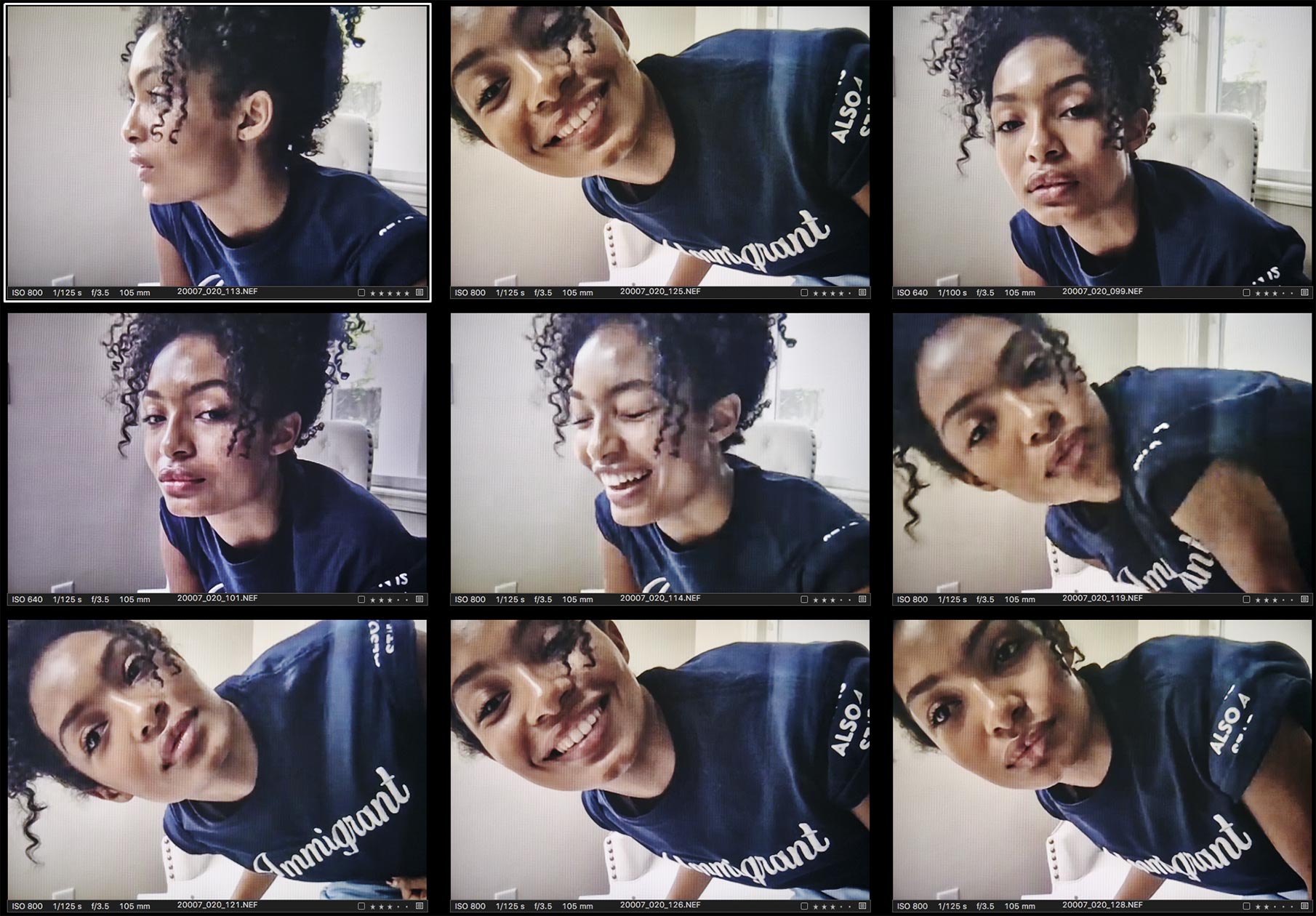

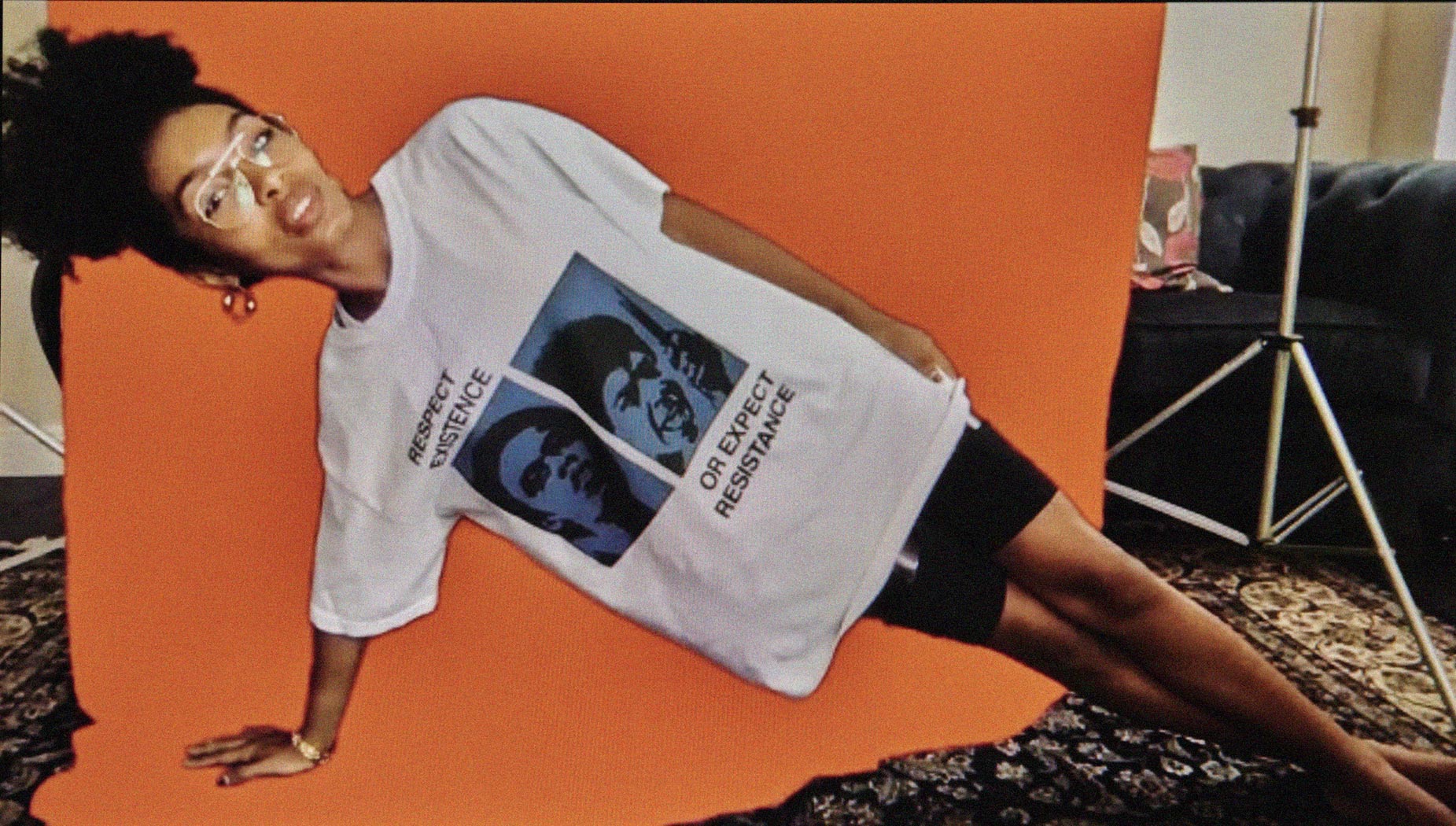

creative direction + photography

MARY ROZZI

What We May Learn From a Pandemic, with YARA SHAHIDI

TSI and Yara Shahidi team up for an innovative Zoom photoshoot and interview that speaks to interconnection, activism, and meaningful creation during the global crisis.

media + culture director

SHIV LYONS

featuring

YARA SHAHIDI

Yara Shahidi— best known as an actor for her role in Black-ish and its spinoff Grown-ish – is also an activist dedicated to using her considerable platform. At 20, she is emblematic of the passionate change makers that define her generation: intellectually curious and unafraid to take on topics that are complex and critical (a favorite thing for journalists to point out about her is that her 18th birthday was, quite literally, a voter registration party).

This entirely Zoom-hosted photoshoot and interview reflects all of our – The September Issues’ team, Yara and the whole Shahidi family – desire to create during the pandemic in a meaningful way. Our collaboration occurred between a rainy evening in a flat in London, a cramped office in the Midwest where the trees outside were just starting to bloom, and a family home on a foggy day in Los Angeles. From our separate corners of the world, we worked together to make something, a document of the moment, in a new spirit of community and creative exchange.

Interview:

THEA SASS-AINSWORTH: Yara, thank you so much for talking to me after the shoot. I know that can be a little tiring, even if it’s on Zoom!

YARA SHAHIDI: No, of course! It went so seamlessly.

THEA: It really did. We’re making the future here and now. First off—how are you? I feel like that’s how all my conversations start these days, with a general wellness check-in.

YARA: I totally get that. I’m good! I’m pretty grateful to be feeling pretty good right now. I know a lot’s happening in the world, but just to be in a house with my family and for us to be together…. I guess I describe it as like, it’s crazy to be aware of what’s happening in the world right now, and to be affected by it, and to know people—both extremely close, and extended family—who are affected by it. But I’m grateful to be in a position where I get to isolate with my family, all together. We know so many people who are isolating alone, or who can’t isolate, so yeah. Pretty good. We do a lot of dance parties in the Shahidi household. With my middle brother Sayeed as a guest, so it’s been pretty productive time (laughs).

THEA:You’re so busy as a person. How has it been to slow down and pause a little bit in this way?

YARA: Just to have the opportunity to pause has been really great. Not much has actually slowed down. It just shifted. I think the one thing, amongst many things, that just living during this time has really reaffirmed, is the importance of being so purpose driven in whatever you’re doing… the epiphany of—okay, what are we contributing right now? What is the purpose of it? I think being here has shifted what can be important.

THEA: I think that’s so true. So many of us are turning to art even if it’s a Netflix binge of Tiger King, or whatever…

YARA: Right!

THEA: …just to cope with the shrinking of our horizons. How does that resonate with you, as someone who is a huge part of this creation of content?

YARA: It really resonates. As somebody who’s first hand influenced by what I intake, I know how careful I have to be, and I think I similarly try to take that level of responsibility into what I make. What is the greater message of this, and how do we make these moments feel accessible. That’s been as simple as giving people the freedom to live on-screen, because for so long, there’s been so many characters and their intersections that have had to serve a very particular purpose of like, “I’m telling you this story of what it means to be of this identity,” versus that acknowledgement of—of course, me being black and Iranian will undoubtedly affect everything about my perspective in the world, and at the same time it is such a part of who I am that we have to move past that conversation to just kind of get at what it looks like to exist in the world. It’s like, how do we continue to give space for people who are not only a part of our community, but people who are part of communities that I’m not personally a part of.

“I think the thing this pandemic has done is call attention to the way we choose to define community, in a way that can be very productive, but also it’s a process in which you have to be very self-aware.”

THEA: In terms of access, do you see now, with all of us turning to our virtual realities so much more, does that change access? Does that shift the landscape?

YARA: It does! In positive ways and in negative ways. I feel like social media has always been a beautiful double edged sword. I do have to say I love seeing passionate young people. When I think about this generation of change makers, I feel like the internet has been integral, because we’ve become aware of each other. Even though there are people that are still being erased from the story of activism and such, I think it happens less often now, because there are ways for us to bring attention to people’s incredible work. And I’ve been so educated from what I’ve continued to learn from my peers, that I don’t think I would have had the opportunity to otherwise be in conversation with. I think at the same time, we can get comfortable with a false sense of accessibility. Right now has highlighted the fact that access to the internet isn’t a given, access to things that seem so naturally integral to our lives… like, having a decent wifi connection, or having a computer or a smartphone you can go onto. But I think now, in a time when pretty much everybody has been dependent on technology, it’s really highlighted the fact that things that we thought of as a given really aren’t, and that there’s even a hierarchy in access to that. In that regard, there’s still work to be done.

THEA: Absolutely. I was reading something the other day where they said, “pandemics are democratizing,” but it’s strange because while it is democratizing, it also underscores the harsh inequities of our society.

YARA: Yeah, I was reading something similar… It’s something that my family has talked about all the time. Ever since I was little they always said, “abundance has to flow.” They’ve always talked about this idea of, in order to receive you must constantly be giving. Because nothing is meant to be laid in the hands of one person. That’s antithetical to how the world is supposed to work. But I think right now, when resources have been highlighted—people who have resources, people that don’t have resources—it’s been interesting to even think about space as something that is so not democratized. It’s not that it’s something we weren’t aware of before, but to see the privilege of space, of being able to maintain certain measures, has been really eye opening. As a family, too, it’s inspired very specific conversations for what it looks like to be of service right now, knowing that we have the privilege to be here right now, and knowing that that’s something that cannot be taken for granted. To be responsible and say—okay, what are we going to do for the many communities that are affected? What does action look like now?

THEA: One hundred percent. I mean, do humans strike you as adaptable? Have you seen that during this crisis?

YARA: I do feel like we’re adaptable. I think seeing the coming together during this crisis has been particularly inspiring. I listen to this one podcast called “Kind World,” it’s so sweet—but I’ve loved listening to it now because it’s highlighted the importance of acts of kindness when we are all in this situation, of people going above and beyond, of saying, “this is my duty”. I feel it’s my duty to my neighbor, to my friend, to my family member, to this person I don’t know. And so I think the thing this pandemic has done is call attention to the way we choose to define community. What does [community] look like now, when there’s so many intersections of people being affected by this and to varying degrees?

“As somebody who’s first hand influenced by what I intake, I know how careful I have to be, and I think I similarly try to take that level of responsibility into what I make.”

THEA: Right? I feel like the dialogue has to shift. And okay, I know you’re really into history. Has looking back to history been helpful for you in contextualizing this time?

YARA: Oh, looking back to history is what I do if ANYTHING slightly out of the ordinary happens, because it is my deep belief that not much is new in this world. I think our context shifts of course, but in terms of actual occurrences… It’s now really become a habit of mine to turn to the past, because there have been generations that have gone through something not exactly like this pandemic, per se, but have endured mass social disruption. In a way that can at least be learned from, as a helpful foundation for us to figure how we adapt in this time. What worked, what was successful. I remember even talking to my grandparents about the Vietnam War… They were asking themselves the same questions of, what does it look like to be a responsible community member right now, what does it look like to put on pause the things that I expect in my life, to intentionally halt all those things that I felt I had the privilege to have? On both sides of my family, they’ve both kind of mentioned this moment, of saying that: these have been questions that have come up time and time again, and that it’s important to turn to our historical context to kind of figure out what our response is right now.

THEA: You’ve said before that policy is personal—how do you see that playing out even more, now, during something like this pandemic?

YARA: Yeah, I mean, that’s why Eighteen x 18 and my voter registration work has been really important to me, because politics have been made to feel super distant—intentionally. Like, it’s made to seem like something that happens in D.C., behind closed doors. All of that feels very intentional, because it leaves communities out of the conversation. It’s really counterintuitive, because I don’t know anything much more personal than politics. We’re seeing the fact that these policies are affecting whether you have access to healthcare. These policies are affecting whether or not you can pay your rent, and have a roof over your head. These policies are affecting what your education experience is like, what you can expect from your workplace. What an equitable world looks like. There’s this strange chasm between how politics happens, as something that’s super abstract, feels super hypothetical, and how it’s enacted. I mean, we see right now, as we’ve seen the places in which great policy has done a great job, and we’ve also seen its failures. This isn’t just a matter of what’s happening in this pandemic right now, it’s a matter of all of these systems that have been in place—where privilege is one group over another—have started to come to light in a life-threatening way.

THEA: Is there something during this time that has brought you particular comfort, or joy?

YARA: Mhmm. I love the fact that I have a family that I love and like. I’m happy to be with my family right now. But a couple things have brought me joy. Talking to my brothers about what it looks like to take action right now—it’s been a true brainstorm in the household, of what we can do for our world at large. It’s something that we talk about every day. Also I’ve been turning to social media, because not only have people been making great content about what’s happening, but there have been people that have taken such incredible action. I’ve been pulling inspiration from, and finding joy in, the people that have been on the ground, and on the front lines, and celebrating them. Also I think, as oxymoronic as it may seem, and how depressing the news is, I think staying informed has brought me joy, because it’s refined what I can do to be in service, by staying in touch with what’s actually happening.

THEA: For you though, was there ever a point where it was hard for you to pull yourself out of your own personal grief and disappointment, in this time?

YARA: I think about this consistently, because I do have a very global family. One way or another, regardless of what’s happening in the world, it feels like it affects me personally, just because it inevitably affects someone in my friend or family group. We’ve had this conversation a lot in our household—I feel as though the way I’ve been raised is such an anomaly, in terms of having parents that are aware of the fact that the way we discuss identity is changing and shifting. It’s always been a two-way street in terms of educating each other, and ourselves. We’ve always had a family that’s really emphasized the importance of extending past ourselves and our family to be of service to communities that may relate to us directly and that may not. Because of that, I walk around with base assumptions that I have to check because I come from this family that is self aware, that is always looking to be better, and is always looking to be as inclusive as possible. I want to maintain those values that have always been instilled in me, while acknowledging that when I’m speaking about a topic, that this isn’t everybody’s given reality, and the importance of acknowledging that. It means that the advice that I give can’t be as simple as “believe in yourself”, because there are systemic things that my family has intentionally tried to circumvent for me. So that’s my long-winded way of saying, yes I’m constantly in a process of trying to acknowledge how my personal experience influences the way I look at a topic.

THEA: Totally.. is that advice that you would give to those that are struggling right now?

YARA: It’s advice that I’d particularly share with people who have the privilege to be in the conversation that I am in right now, of saying “how do we help the world?” I think when you are already in a position of being oppressed either way, or having a lack of resources, then I don’t think it is on you to think outside of your experience. If anything, I think it’s necessary to share the specificities of your experience. We have to be honest about our experiences, and that’s really powerful, and very helpful. But it’s also, how do I consistently educate myself, through conversation, or whether it’s just passing the mic sometimes(laughs), ‘cause this isn’t for me to speak on.

“Abundance has to flow. They’ve always talked about this idea of, in order to receive you must constantly be giving. Because nothing is meant to be laid in the hands of one person.”

THEA: That’s really important. I was talking to someone the other day, and she was like: you gotta know what you don’t know, because otherwise, it’s dangerous.

YARA: Precisely. That is the most concise way of saying something that I spent five minutes trying to explain!

THEA: Okay, big question, so take it however you want. Do you think experiencing this pandemic will shift the future for your generation specifically?

YARA: Undoubtedly, because for Gen Z this is happening at such a fundamental point in our lives. And to be a generation that is already so interconnected, I feel as though we have seen the effects of this pandemic, not only on such personal levels, but on such broad scales. Because we are such an interconnected generation, I think this hits home in so many ways, whether it personally hits you, or whether it’s just the fact that we are all aware of each other’s circumstances, and seeing how it’s affecting different people. Because it has completely halted our economy, our jobs, our ability to be social humans, it really shifts for us going forward what structures aren’t working. It’s been, in a way where you wish it never had to happen, strangely a diagnostic on what’s worked, and what values are pretty trivial. This, I feel like, if anything, will further our already present adamants, that structures have to shift, and that we cannot wait until another crisis to say that it’s necessary to shift.

THEA: Absolutely. Okay, last thing. This is a concept that as a magazine has driven us, as women artists and creators. What does the power of the femme mean to you?

YARA: I was at a conference about “woman of the year” and it got me thinking about what womanhood means. Womanhood is such a broad term because it does include what it means to be femme, what it means to be gender fluid. It doesn’t look like the binary that we’re used to. The conclusion that I’ve come to, that I feel like I stand by, even after a couple months of thinking about it, is that it means the power of saying no. Especially in a system in which there is so much that we are expected to be complacent with. When I look at, whether it be the arts or activist world, whatever field, I think the power of the femme really speaks to the power of saying no, and having such a productive no. Our no shapes systems to be more equitable. Our no isn’t just a, “I’m not okay with that”, it’s “let me tell you how we’re supposed to be running and operating”. If anything, a re-envisioning and a reimagining of a future that’s so predestined.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.